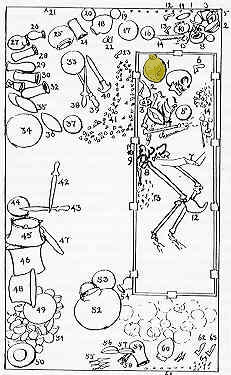

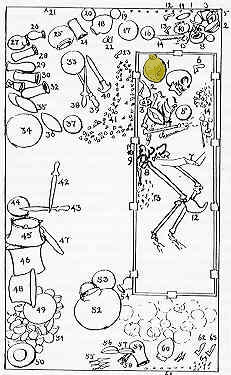

The Grave of Meskalamdug

Sumerian Civilization

"The city state in earliest Mesopotamia was organized economically and

religiously into temple communities headed by a priestly representative

of the patron deity or deities of the city. A political assembly of

citizens or elders also ruled. Later this [primitive] combination of

theocracy and democracy in the cities gave way to rule by a Lugal a

title meaning King, used by sovereigns claiming wider domination."

Sumerian deities were closely bound to natural phenomena, the powers

of creativity, fertility, and forces confronted in the cosmos. Even at

the dawn of history, however, these gods were conceived for the most part

in human form and were organized in a cosmic state reflecting the social

forms of pre-monarchical Sumer. The world of the gods was a macrocosm of

Sumer where earthly temples, counterparts of cosmic abodes of the gods,

forged links between the two realms. The assembly; Enlil, young 'Lord

Storm,' the violent as well as life-giving air; Ninkhursag or Ninmakh,

the great mother, personification of the fertility of the earth; and

Enki, god of underground waters, the source of the "masculine" powers of

creativity in the earth. Another important triad consisted of Nanna

(moon), Itu (Sun), and Inanna (Venus). The chief cult-dramas included the

cosmogonic battle enacted in the New Year's festival, in which Enlil,

later Marduk of Babylon, established order by defeating the powers of

chaos, and assumed kingship. Another important cycle of rites had to do

with Dumuzi (Tammuz), with laments over death, celebration of the return

to life of the young god and his union with Inanna which assured spring's

resurgent life." (Encyclopedia of World History, Ancient, Medieval, and

Modern: Chronologically Arranged. Compiled and Edited by William L.

Langer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1972. p29.)

Sacrificial practices

Who were the victims of sacrificial burial? What purpose did their

death serve? Some debate exists over the reason behind Sumerian human

sacrifice, a practice unique to this time period in Mesopotamia, although

we know that other concurrent cultures performed similar practices.

Perhaps, as discussed in Moorey's article "What do we know about the

people buried in the Royal Cemetery ?" the victims fulfilled a

sacrificial rite based on their social status in the society. Hypotheses

propose that the dead served as substitute kings and queens/ priests or

priestesses (depending on the theory to which you subscribe). As with

the buried jewelry, vehicles and other costly items, the sacrificial

humans might have served as possessions for the dead in the afterlife, or

gifts for the deities of the Underworld whom the patrons of the tombs

(according to Woolley) hoped to encounter.

Sacrificial practices

Who were the victims of sacrificial burial? What purpose did their

death serve? Some debate exists over the reason behind Sumerian human

sacrifice, a practice unique to this time period in Mesopotamia, although

we know that other concurrent cultures performed similar practices.

Perhaps, as discussed in Moorey's article "What do we know about the

people buried in the Royal Cemetery ?" the victims fulfilled a

sacrificial rite based on their social status in the society. Hypotheses

propose that the dead served as substitute kings and queens/ priests or

priestesses (depending on the theory to which you subscribe). As with

the buried jewelry, vehicles and other costly items, the sacrificial

humans might have served as possessions for the dead in the afterlife, or

gifts for the deities of the Underworld whom the patrons of the tombs

(according to Woolley) hoped to encounter.

Click on the illustration of Meskalamdug's Grave for additional views

of a golden "wig" excavated by Wooley.